|

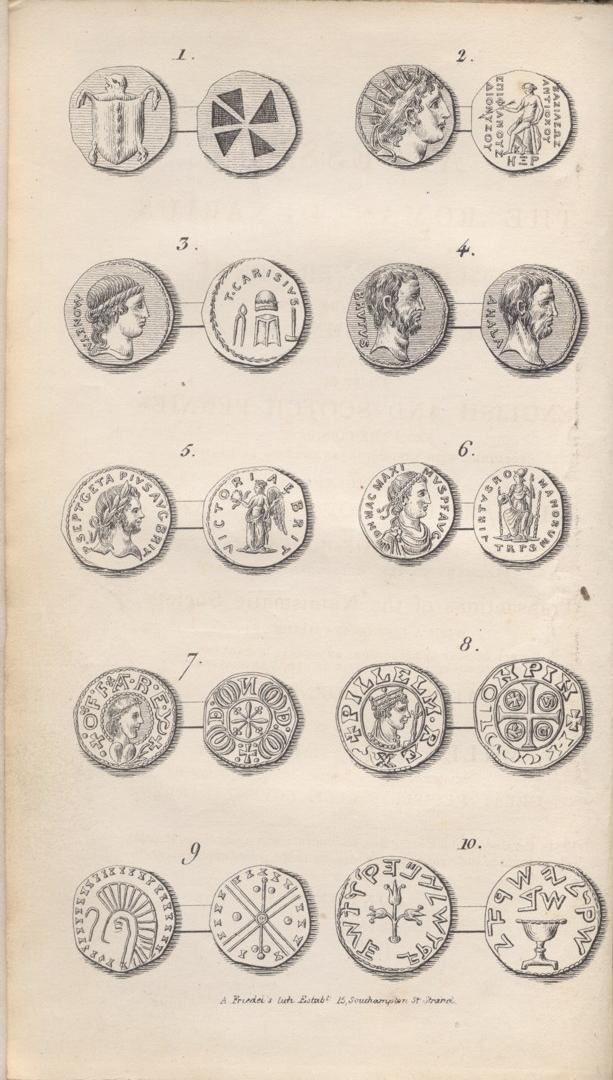

No. 1. A Drachma of AEgina, of the earliest Greek work. On the obverse, a Tortoise, of barbarous execution. The reverse, rude indentations.

No.2. Drachma of Antiochus VI.(EΠIΦANOYΣ ΔIONYΣOY) of Syria. This brilliant gem, the production of the early Greek mint, is from the collection of the late Mr. Abraham Edmonds, of Castle Street, Southwark; and by the special permission of Mrs. Edmonds, here engraved. In its preservation it is unique; in its production almost inimitable,—and may truly be considered the chef d’oeuvre of Grecian art; indeed, the face on this medal is of such exquisite design, and of such extraordinary beauty, that, one is led to suppose the artist had the bust of Apollo, or of some other model of perfection, in his view while engraving it. The obverse represents the head of Antiochus Epiphanes Dionysus, the youthful King of Syria, adorned with a radiated Crown and a Fillet,—the Grecian emblem of sovereignty. On the reverse, a seated figure, with the king’s name and title: BAΣIΛEΩΣ ANTIOXOY EΠIΦANOYΣ ΔIONYΣOY under the letters HΣP, the monogram, or abbreviation for the place of mintage.

Vaillant, in his account of the Syrian Kings, describes this figure as being that of Apollo, seated on what he designates a Cortyna; but I am tempted to differ with this high and respected authority, and to presume it to be a female figure, with the hair braided in the Grecian style and hanging over her shoulders,—probably that of Diana, having the bow and arrow. This figure differs from that on the Drachma of the same Prince engraved by Bartolozzi, inasmuch as he therein is represented in a state of nudity, and without the ringlets; this has, at least, a very little drapery.

No. 3. A Denarius of the Carisia family; a common but very interesting coin, bearing on the obverse, the head of Moneta, with name; and on the reverse, the implements used by the Romans in their coinage, viz. the two dies, with hammer and pincers, and the name of the family, the whole within a garland. How it was possible, with the hammer here represented, to give that effect to the coinage which we meet with in the Roman series, I know not, still, doubtless it is a correct representation of that used in the Roman mint.

No. 4, represents a coin of the Junia family, bearing the heads of Brutus and Ahala; not the assassin Marcus Brutus, who stabbed his bosom friend and reputed father, but his progenitor. This is the Lucius Junius Brutus who doomed his own sons to death, and witnessed the sentence executed on them. Verily, these Romans must have been formed of strange materials. We may imagine the inflexibility of the judge in the condemnation of his sons, from his patriotism and stern love of justice, but we cannot account for the absence of all parental feeling in the father, to witness the infliction of their punishment. On the reverse, is the head of Ahala, another worthy, an officer under the Dictator Cincinnatus, who slew Melius for refusing to answer certain political accusations brought againt him.

This Denarius was struck by Marcus Brutus immediately after the murder of Julius Caesar, in tending probably to defend the crime in which he had been a guilty participator, by presenting to the Roman people, the busts of two individuals, whose memory they revered, and whose statues were preserved in the Capitol, 1 and like himself had either directly or indirectly imbrued their hands in blood.

Marcus Brutus likewise struck other pieces commemorative of and in allusion to this eventful period; (these coins are properly classified as Consular, still their date would permit them without impropriety to be arranged with the Imperial Series, as they were certainly struck subsequently to those of Julius Caesar, with whose coins commences the latter class). One Denarius bears on the obverse the head of his favorite Deity, “the Goddess of his idolatry,” “Libertas;” on the reverse, Lucius Junius Brutus attended by the Lictors. Another has his own head, with that of Lucius Brutus on the reverse; but the most curious is that with his head on the obverse, and on the reverse, the Cap of Liberty (the Bonnet rouge of modern times) between two daggers, with this inscriptions, EID. MART. On this piece, Marcus Brutus is represented with that ferocity depicted in his countenance which one would expect to find in such a man.

These coins will be found finely pourtrayed in the “Thesaurus Morellianus, sive Familiarum Romanarum Numismata Omnia, being the coins of the Consular Families, beautifully engraved, and excellently described by Andrea Morellio.

This curious Denarius, last mentioned, is from the collection of my very earliest and kind friend, the late Mr. John Peckham of Slough: it is one of a number of his coins which, when a boy, I have almost worshipped, (not out of respect to the characters it pourtrays), and the possession of this piece, at that time, would have completely un settled me; it would have haunted me in my very dreams: that day is gone; that feeling never can return. Enthusiasm is now sobered down to admiration. I have had too many fine coins pass through my hands for the pleasurable excitement I speak of to have been kept up undiminished. The whole of Mr. Peckham’s collection came into my possession by purchase subsequently to his decease, 2 and some few of the coins I preserve, as a memento of one of the best of friends, whose memory I revere, and of whom I cannot speak too highly.

As this trifle is published not altogether with a view to sale or profit, I must be permitted a digression or two. In looking the other day over my debtor and creditor account of benefits received, I found in my balance sheet the names of many individuals to whom I am much indebted; if not in a pecuniary view, still in that of having kindnesses bestowed upon me, which I have not, to my own satisfaction, repaid. I must therefore take advantage of the channel which this publication affords me, of publicly and gratefully acknowledging the same with my best thanks, regretting that the return is by no means commensurate with the advantages received.

It may perhaps be gratifying to some of my readers, and I speak, I trust, with that modesty that becomes me, to receive some account of the family of the Bruti and of Ahala, who have been mentioned in the foregoing descriptions of Denarii impressed with their effigies. I venture therefore to mention that Lucius Junius Brutus was the son of Marcus Junius and Tarquinia, the second daughter of Tarquin Priscus. The father, with his eldest son, were murdered by Tarquin the Proud and Lucius, unable to revenge their death, pretended to be insane. This artifice saved his life; he was called BRVTVS for his stupidity, which he however soon afterwards shewed to be feigned.

When Lucretia killed herself, 509 years before Christ, in consequence of the brutality of Tarquin, Brutus snatched the dagger from the wounds, and swore upon the reeking blade immortal hatred to the royal family. His example was followed, the Tarquins were proscribed by a decree of the Senate, and the royal authority vested in the hands of Consuls chosen from Patrician families. Brutus, in his consular office, made the people swear they never would again submit to kingly authority; but the first who violated their oath were in his own family. His sons conspired with the Tuscan Ambassador to restore the Tarquins, and, when discovered, they were tried and condemned before their father, who himself attended at their execution. This occurred 465 years before Christ.

This Brutus was subsequently slain in a battle fought between the Romans and the Tarquins.

Tarquinius Priscus was the fifth King of Rome, and son of Demaratus, a native of Greece. His first name was Lucumon, but this he changed when, by the advice of his wife Tanaquil, he had come to Rome. He called himself Lucius, and assumed the surname of Tarquinius, because born in the town of Tarquinii, in Etruria.

Marcus Junius Brutus was married to Servilia, the sister of Cato, by whom he had a son and two daughters. After the death of Sylla, he was besieged in Mutina by Pompey, by whose orders, after surrender, he was put to death.

His son, of the same name, (and whose coins are alluded to) seemed to inherit the republican principles of his great progenitor. He was one of the murderers of Julius Caesar which deed was perpetrated 44 years before the christian era. The mother of Marcus Junius Brutus, Servilia, the sister of Cato, was greatly enamoured of Julius Caesar, and from the intimacy that existed between them, some have supposed that the Dictator was the father of this Marcus Junius Brutus.

Ahala is the surname of the Servilia family at Rome. Servilius Ahala was Master of the Horse to the Dictator Cincinnatus. When Melius refused to appear before the Dictator, to answer the accusations which were brought against him on suspicion of his aspiring to tyranny, Ahala slew him in the midst of the people, whose protection he claimed.

This took place 439 years before Christ. Ahala was accused for this murder, and banished, but this sentence was afterwards repealed. He was subsequently raised to the Dictatorship. 3

No. 5. A Denarius of Geta, struck after his father’s expedition to Britain, and particularly relating to that event. On the obverse is the head of Geta, regarding his left, laureated, and with a beard.

This Prince is generally represented on his silver coins without one. On the coin before me (which is from my own private cabinet) he is made to appear like a man of forty, when in reality at his death he was only twenty-three years old. His name and titles are given as follows—P. SEPT. GETA PIVS AVG. BRIT., Publius Septimius Geta Pius Augustus Britannicus.

On the reverse, a winged Victory, with her right arm extended, and presenting a crown of laurel; whilst in her left she holds a palm branch, encircled by the legend VICTORIAE BRIT., Victoria Britannicae.

His father, the Emperor, Sept. Severus, agitated and alarmed by the continual and inveterate enmity manifested by his two sons against each other, gladly embraced, as Gibbon relates, any pretext for withdrawing those hopeful youths from the licentiousness of the Roman capital. An opportunity was not long wanting. The Caledonians had revolted: Severus was determined to chastise them in person, and, attended by Caracalla and Geta, he lived long enough to obtain a victory at an immense sacrifice, but not the homage of the hardy Scot, who again appeared in arms, and was only saved from extirpation by the death of the conqueror at York, leaving his sons to return with hasty strides to Rome, there to revel in excesses which ended in the murder of Geta by his brother. This coin, of course, was intended to perpetuate and record Geta’s participation in the victory here so significantly alluded to. Very similar coins occur of his father, and his brother Caracalla.

This Denarius is well known, and has been frequently engraved; but I feel assured that no excuse is required for introducing it here, as it relates so particularly to our own country.

No. 6. A coin of Magnus Maximus, an usurper in Gaul, A. D. 385. This piece is here introduced merely to convey to the reader a specimen of the Roman coinage at a late period of the empire, and to shew how closely the Saxons followed in the weight of their Pennies. This coin weighing 1 dwt. 2 grs., two grains only above the standard weight of the Saxon, Penny, (hence the word Pennyweight); in fact, I possess a Penny of Ethelred II., and another of, the Confessor, each weighing nearly two grains above the proper Pennyweight; but, on an average, the Saxon Pennies will be found to be two or three grains less than the standard weight, even if finely preserved.

This Denarius of Magnus Maximus shews his bust clothed in armour, with his head laureated, and looking t his left, with this legend, D. N. MAG. MAXIMVS P. F. AVG. (Dominus Noster Magnus Maximus Pius Felix Augustus). On the reverse is a seated figure, holding in the right hand a globe, surmounted with a small Victory; and on the left, a staff or spear, with the following legend, VIRTVS ROMANORVM. The exergue contains the place of mintage abbreviated, T. R. P. S. (Treveris Pecunia Signata) or, Money struck at Trevers.

These coins, although common here, are considered rather scarce on the Continent, which is the more singular, as there they were struck.

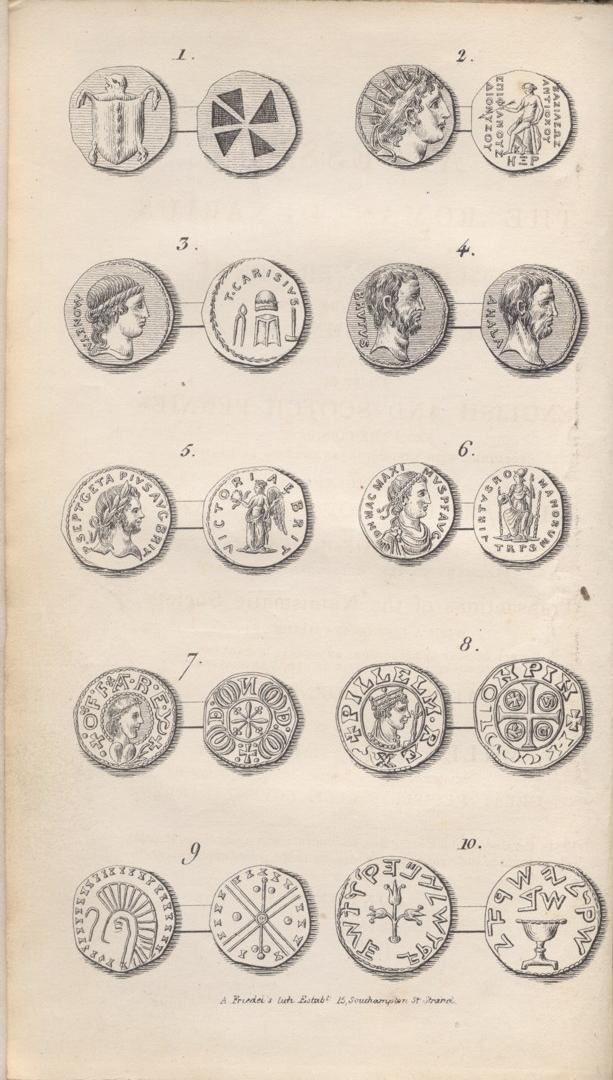

No. 7. A Saxon Penny of Offa, King of Mercia. On the obverse, the bust of the king in profile, looking (as a herald would describe) to the sinister, or the left side. The head adorned with a fillet, composed of a double row of pearls; the hair apparently falling behind in a club—(It would seem this monarch was what in our present time would be termed a regular dandy; and if you ex amine Ruding’s plates of him, you will find his hair twisted into a variety of shapes, more like unto that of a female than of a Saxon King of Mercia: the probability is that his connexion with the court of Rome induced him to ape this style). He is represented as having what appears to be a branch in his hand, and around the bust his name and title. On the reverse, an ornamental cross, surmounted with devices, and the letters of the moneyer’s name Dud.

This rare, and as far as it relates to the type, unique coin, differs very materially from any of the same king engraved in Ruding, and before this was unpublished. It passed through my hands some years since, and the present possessor has kindly permitted me to engrave it.

No. 8. An extremely rare Penny of the Conqueror: one of a large quantity discovered at Bea worth, near Winchester. The rarity of this Penny consists in its being of what is termed the pax type, and having the head in profile, instead of full faced; this peculiar type was unknown until this discovery took place, and they are still very rare. On the obverse is the bust of the king, with name and title PILLELM. REX. On the reverse, a cross, and between its limbs are four circular compartments, with the letters PAXS, in direct imitation of his predecessor Harold II. The legend is composed of the place of mintage ON. PINC. i. e. WINC. (Winchester). The Saxon W differing but little, if at all, from the modern P.

This coin is in the highest state of preservation, and from a very celebrated collection; but unfortunately the bust of the sovereign and the name of the moneyer “Linold” are not struck up, consequently, a little imperfect, and this is a very common occurrence with the Pennies of our early kings.

No. 9. A very rude Irish Penny, discovered some few years since in Ireland, with many others. It is doubtless Prelatical, as on the obverse we find a head of the most barbarous execution, and before it a crosier, with short straight strokes instead of letters in the usual place of the legend. On the reverse is a long double cross, with pellets and strokes similar to those on the obverse.

This coin is extremely thin, and weighs only seven grains. Of about one hundred which came into my possession, this appears the average weight, but some are still lighter.

I am not aware that these gems of the Emerald isle have been engraved before.

No. 10. A very rare, curious, and extremely interesting coin, the antient Jewish Shekel, solicits peculiar attention. It is a silver coin of Simon Maccabaeus the High Priest and Prince of the Jews. Its weight is 219 grains. The specimen here referred to was struck 142 years before the Christian era. On the obverse is represented the golden pot of Manna, and over it the date of the coin, expressed by the current year of the independence of the Jews, a year coinciding with that of Simon’s reign and pontificate. As to the date itself, it is comprised in two Samaritan characters, to be read from right to left, contrary to the mode of reading European languages. The first letter, similar to our W is that of Shin, or SH of the Hebrew word “Shenath,” signifying year; the second “Beth,” used as a numeral to express two, and thus the two characters are to be read Shenath Shetaim, which phrase means the second year. The legend on the same side, is likewise expressed in Samaritan letters, and begins with Shin, the letter similar to W, and is as follows, SH.K.L. I. S.R.A.L, that is, SHeKeL ISRAeL, the Shekel of Israel

On the reverse is beheld a trifed branch of the Almond tree with blossoms, such being intended as the representation of Aaron’s rod that budded; in connection with which is the following legend in Samaritan characters, J.R.U. S.L.I.M H-K.D.O. SH.H, that is JeRUSaLaIM Ha-KeDOSHaH, meaning Jerusalem the Holy.

Although the above curious piece may bear no affinity to the Greek Drachma, the Roman Denarius, or any other coin here treated of, I could not avoid presenting it, if only to correct a false notion that is prevalent, that a coin of modern fabrication, which often occurs, is the Jewish Shekel.

The false coin I allude to, is somewhat smaller than our half-crown, weighing from 160 to 185 grains. On the obverse is a Censer, from which the smoke of incense arises, encircled by the following legend in the Hebrew characters, (but which characters are badly formed,) “SHeKeL ISRAeL. On the reverse, is seen a large branch of the Almond tree, with the accompanying legend, “JeRUSaLaIM Ha-KeDOSHaH.”

When and where these coins were first fabricated, I believe no one can accurately state, and that they are fabrications there is not a moment’s doubt, although the Jews, generally speaking, consider them as their Shekel, yet in this they are deceived. There are two or three varieties of these false coins, but as there is a great similarity between them, it may be sufficient for the information of the public, to describe this type only.

Simon, or Simeon, of the house of the Maccabees, (see the first book of the Maccabees,) was the first Jewish Prince who struck money; previous to his time, there can be no doubt that the Shekel was, according to its appellation, a weight only, and in no specific form. This is borne out in evidence through nearly the whole of the Old Testament, commencing with the book of Genesis, and concluding with that of Amos. In carefully examining the Bible, I find the Shekel named in no less than sixty different places, 4 but the following extracts will probably be sufficient for our purpose. Relative to Rebecca, the sacred historian, in the twenty-second verse of the twenty-fourth chapter of Genesis, says, “The man took a golden ear of half a shekel weight, and two bracelets for her hands of ten shekels weight of gold.” Again, in the first book of Samuel, at the fifth and seventh verses, Goliath’s helmet and coat of arms weighed five thousand shekels of brass,”—”and his spear’s head six hundred shekels of iron.”

In the Apochrypha, we find the shekel assuming the shape of a coin, (see the Plate No. 10,) Antiochus, sixth King of Syria, granting Simon the privilege of issuing money with his own name. “I give thee leave also to strike money for thy country with thine own stamp.” Fifteenth chapter of the first book of Maccabees, and sixth verse.

Of Simon we have the Shekel, the Bekah or half-shekel, and the quarter thereof, in silver. These coins are all very rare; likewise three different sizes in copper, some large, and these also are scarce. His descendants, Alexander, Jannaeus and Jonathan, struck copper only, and those of small size. John, the son of Simon, struck no coins; at least none have reached us.

From the time of the Maccaebean Princes to that period when Judea again had her kings, who were tributaries to the Roman Emperors, we obtain no Jewish coins; of those sovereigns, the following struck them :—Antigonus, Herod I. (the butchering Herod, falsely called the great), Herod II. and III., Philip the Tetrarch, Agrippa I. and II., and Zenodorus the Tetrarch. They are of copper, and small in size, and thereon we obtain portraits of Philip, Agrippa I., Herod III., and Zenodorus. On their obverse are the heads of the Emperors to whom they were tributary, but they are poor things, and very rare. Of none of the other kings have we any portraits.

Footnotes:

1 There can be no doubt but this is an accurate portrait of Lucius J. Brutus, and in all likelihood taken from his statue, as well as that of Ahala, alluded to by Cicero in his second Philippic, chapter ii.

2 I had the melancholy task of attending the remains of my kind old friend to the grave; he was interred in the chancel of Upton Church, Bucks, close by the side of the celebrated astronomer Herschel.

3 A few of my authorities for these references may suffice Livy I. c. 31, 46, and 56—ii. c. 1; Dionys. Hal. iii. c. 59—iv. c. 48—and v.; Corn. Nep. in Attic. 8; Pliny, viii. c. 41; Plutarch, in Brutus and Caesar; and Aen. vi. v. 817 and 818.

4 Genesis xxiii. 15. xxiv. 22. Exodus xxi. 32. xxvi. 24, 25, 26. xxx. 13, 15, 23, 24. Leviticus v. 15. xxvii. 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 16. 25. Numbers iii. 47, 50. vii. 13, 14, 19, 25, 31, 37. xviii. 16. xx. 26, 32, 38, 44, 50, 56, 62, 68, 74, 80. Deuteronomy xxii. 19, 29. Joshua vii. 21. Judges viii. 26. xvii. 2, 3, 10. 1 Samuel ix. 8. xvii: 5, 7. 2 Samuel xiv. 26. xviii. 11. xxiv. 24. 1 Kings x. 16. 2 Kings vii. 1. xv. 20. 1 Chronicles xxi. 25. Nehemiah v. 15. x. 32. Jeremiah xxii. 9. Ezekiel iv. 10. xlv. 12. Amos viii. 5.

Table of Contents

|